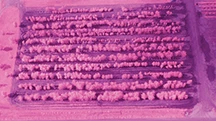

The fallible human eye and hand isn’t too reliable when it comes to creating a straight line. But when crews are laying out a field prior to planting, those lines need to be as straight as possible to help carry out a successful production life.

The fallible human eye and hand isn’t too reliable when it comes to creating a straight line. But when crews are laying out a field prior to planting, those lines need to be as straight as possible to help carry out a successful production life.

This year, Spring Grove Nursery in Mazon, Ill., tried a new process to plant tree rows, which shaved time off the pre-planting process and created precise spacing. The nursery successfully used a tractor with auto steer functionality to help plant a block of trees.

Becky and Jamie Thomas, owners of Spring Grove, have 90 acres of B&B trees in production. The nursery is fortunate to have some innovative technology at its disposal thanks to Becky’s family soybean and corn farm. Becky is a fifth-generation farmer, and her dad, Doug Harford, has been an early adopter of many forms of technology during the last few decades.

“My dad has always been an innovator in agriculture technology,” Becky says. “We were one of the first farms to use no till in the ‘70s. And in the ‘80s when GPS came to corn and soybean farms to help track yields, our farm was one of the first in the country to use it.”

The family corn and soybean farm, which is now run by Becky’s brother, uses a tractor with auto steer functionality. It does more than just drive the tractor, Harford says. Because it’s accurate within an inch, tree rows are precise with perfect spacing based on the GPS coordinates that are programmed into the system.

“It worked fantastic. It saved us a lot of time, and shaved off quite a bit of labor,” she says. “Normally when we are planting trees, we flag the rows and mark the spacing by hand. We have to be very specific on spacing so we can get our equipment in to spray, maintain and dig the trees. If spacing is off a bit, it can get you into trouble a bit down the road.”

The nursery also used GIS (geographic information systems) technology in tandem with the auto steer. GIS allows the Spring Grove crew to track all of the trees planted in the nursery. This will allow the nursery to make a computerized of map of the tree blocks by GPS coordinates of which trees are planted where.

“It also helps keep track of which supplier the trees came from,” says Becky. “GIS will eventually become a valuable tool to manage inventory. Later this year after planting and digging, we’ll get a better handle on all the things GIS can do for us.”

Bird’s-eye view

Spring Grove tried out a second new technology thanks to Becky’s dad and the family corn and soybean farm. Harford flies a gyrocopter, which is equipped with a near infrared (NIR) camera to look at corn and soybean crop health. NIR light is not visible to the human eye. Healthy plant tissue reflects NIR light and unhealthy tissue absorbs NIR, Harford explains. It’s likely applicable to nursery crops, but Spring Grove and Harford haven’t yet realized NIR’s full capabilities for trees.

“In the visible spectrum, we generally know distressed by a change in color from green to yellow for instance, but this takes much more time than sensing with infrared,” he says. “By the time a plant changes color, the stress has done significant damage. The idea behind infrared is to see changes in the plant earlier, when there is still time to manage the problem.

“In the visible spectrum, we generally know distressed by a change in color from green to yellow for instance, but this takes much more time than sensing with infrared,” he says. “By the time a plant changes color, the stress has done significant damage. The idea behind infrared is to see changes in the plant earlier, when there is still time to manage the problem.

“In soybeans, spider mites damage drought-stressed crops, but by the time they turn yellow, it’s too late to treat with insecticide because the infestation has already caused damage. I don’t know if the same is true for nursery crops, but I expect that sucking insects like spider mites might be seen sooner. We may also see problems with irrigation in our holding yard before the tree turns yellow and is unmarketable. Right now these are speculations, and we hope to learn if this is a practical application for infrared technology.”

Dedicated infrared cameras are expensive, so Harford took a regular camera and removed the internal filter that blocks infrared light and replaced it with a filter that blocks visible light.

“There is software available, like Photoshop, but made specifically for infrared that will allow you to modify the picture to bring out more data from the photo,” he explains.

There are many different ways to get an infrared photo, says Harford. Satellite systems (remote-sensing) is a way to cover large areas and market to a broad audience.

“The problem with satellites is the time over the your field is limited, and since they are 25,000 miles above the earth, weather, photograph resolution, and data transfer rates limit the amount of time your field can be photographed,” he says. “Airplanes work well for infrared photography, but it is hard to commercialize that business, because weather, time over field, and short growing seasons limit profitability for the vendor. Small drones have caught the imagination of many, but have not proved to be practical yet. Lots of people are looking at them, because the grower can manage the timing and get immediate results. A new drone system is about $25,000.”

The ROI for the technology such as GIS, auto steer and NIR depends on the size of your operation, Becky says.

“We have an advantage that we can use the technology that’s already in use at the corn and soybean farm,” she says. “But there are so many variables in this business, that any tool you can use to help manage them is useful.”

For more: www.springgrovenursery.com

Do you have an innovative process or piece of machinery?

If so, you can be a part of our continuing series, Project Innovation. Drop me a line and tell me more about it; krodda@gie.net.

Latest from Nursery Management

- The Growth Industry Episode 10: State of the Horticulture Industry

- Tennessee Green Industry Field Day scheduled for June 11

- UTIA and UT Knoxville research teams will develop automated compost monitoring system

- Ken and Deena Altman receive American Floral Endowment Ambassador Award

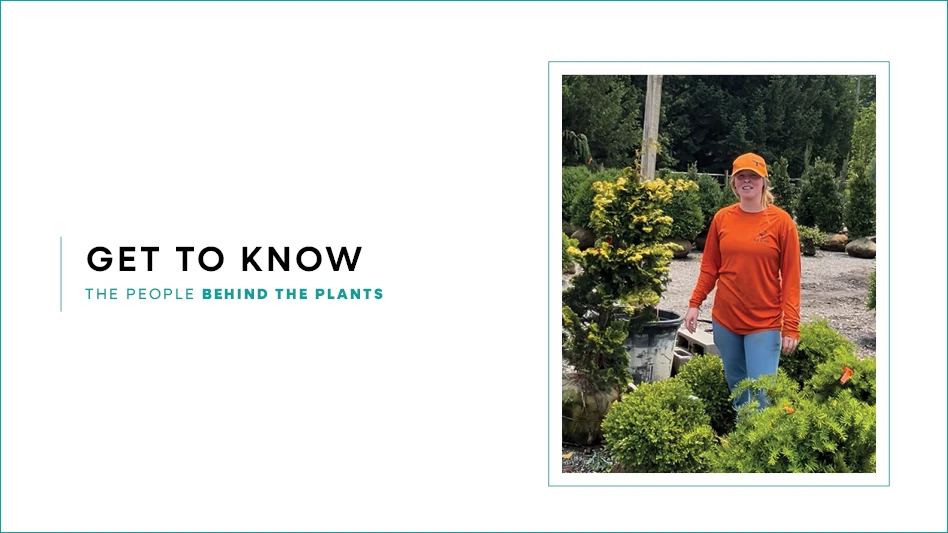

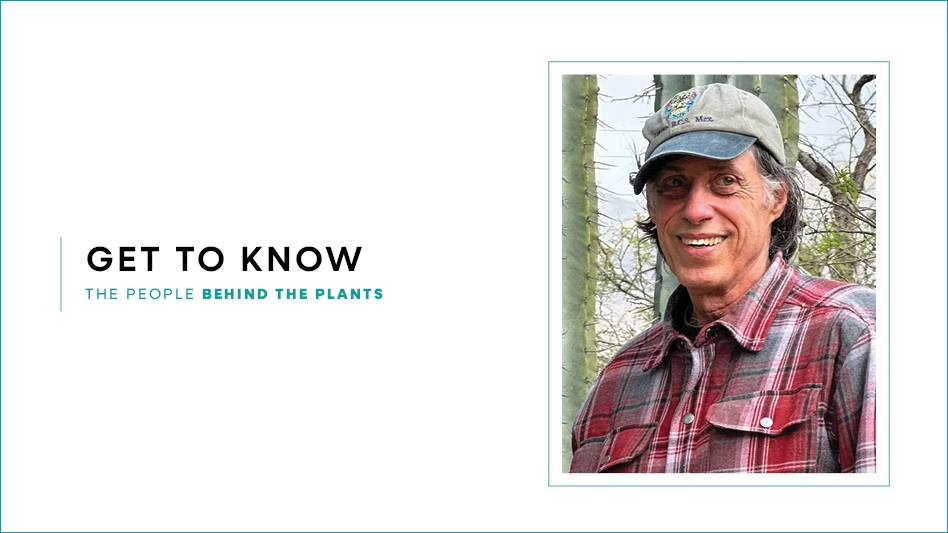

- [SNEAK PEEK] Leading Women of Horticulture: Becky Thomas

- [SNEAK PEEK] Leading Women of Horticulture: Angela Burke

- [SNEAK PEEK] Leading Women of Horticulture: Alexa Patti

- Native before it was cool