Michael A. Dirr

Aesculus pavia habit in flower

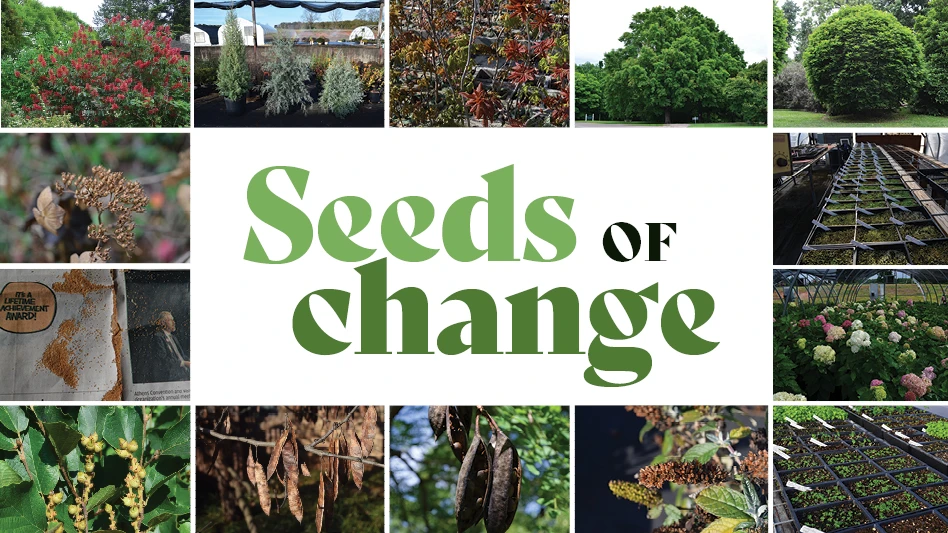

I love seeds and seedlings for the variation they offer to anyone with wild-eyed curiosity “looking” for the next clonal introduction. Without seedling variation, our industry would primarily depend on genetic mutations or “sports.”

In a previous Nursery Management article on Thuja, the numerous sports of ‘Green Giant’ arborvitae were chronicled. Most species do not produce a plethora of these mutants, whereas each seedling is theoretically unique from others within a population. Plantspeople notice the obvious “oddities” that deviate from the norm. Weeping, umbrella, dwarf, pyramidal and fastigiate growth habits occurred within seedlings of Carpinus betulus, European hornbeam. All resulted from the “genetic plasticity” within the species. Another example is Fagus sylvatica, common or European beech, with numerous seed-derived cultivars varying in growth habit and foliage characteristics. The Hillier Manual of Trees and Shrubs (2019) described 38 cultivars of F. sylvatica and none for Fagus grandifolia, American beech. The RHS Plant Finder (2025) listed 46 European beech cultivars available in UK commerce.

The retail nursery industry has to a degree lost touch with the process of seed propagation and production. Certainly, there are superb wholesale woody seedling producers like Bailey, Heritage, JPLN, Evergreen, Forrest Keeling, Superior Trees, native plant nurseries, forestry companies and others, the material utilized primarily for understock, reforestation, wildlife habitats and wetland mitigation.

The retail garden centers are weighed toward cultivars with occasional seedling trees and shrubs. I recently searched the internet for seedling Ilex glabra and found a single southeastern nursery with material (Mellow Marsh Farm, Siler City, N.C.). However, cultivars ‘Compacta’, ‘Densa’, Forever Emerald, Gem Box, Nordic, ‘Shamrock’, Squeeze Box and Strong Box were common. Previous attempts to locate seeds or seedlings of Fothergilla gardenii, F. × intermedia, F. major or F. milleri have been fruitless. Fruits developed on a group of Fothergilla cultivars in the Dirr garden in 2024, but all aborted before maturity. In 2025, I collected seeds from F. × intermedia ‘Malone’. They are currently in warm stratification to be followed by cold and a repeat cycle if necessary. It is impossible to breed/develop new traits without seed. The lone exception in Fothergilla being ‘Blue Shadow’, a sport of ‘Mt. Airy’, with glaucous blue foliage, introduced by Gary Handy, Boring, Oregon.

Theme and variations

Why the enthusiasm for seed and seedling production?

Without the variation inherent in species and hybrids, there would be a paucity of superior clonal/cultivar selections, our nurseries and gardens the poorer. As mentioned, most woody plants offered at retail garden centers are vegetatively propagated clones/cultivars. L. H. Bailey, the great Cornell University Horticulturist, described the term species “as a kind of plant or animal distinct from other kinds in marked or essential features that has good characters of identification and may be assumed to represent in nature a continuing succession of individuals from generation to generation.”

The bell-shaped curve is a graphic way to categorize species characteristics and variability. Based on the “good characteristics of identification,” all/most individuals under the curve carry the leaf, bud, stem, flower and fruit traits that define sugar maple, Acer saccharum. However, significant variation is occasionally manifested under the tails of the curve. The tails are the genetic diamond mines that horticulturists, nursery growers, breeders and gardeners exploit. For example, Newton Sentry’ (‘Columnare’) and ‘Temples Upright’ (‘Monumentale’) are columnar/fastigiate selections. ‘Shawnee’ is globose to rounded. All were embedded in the genome (genes) of Acer saccharum until expressed morphologically/phenotypically and recognized as unique.

In the breeding world, successes and failures are inherent in the ability to manipulate/germinate seeds. I am fascinated by the processes of seed collection, storage and germination. From year to year, seed collected from the same plant may produce different germination results.

Types of seeds

What is a seed?

The shortest answer is a ripened ovule. An ovule contains egg cell(s) and other nuclei which when fertilized by the sperm cells from the pollen parent, develop into the seed. This ripened (fertilized) ovule matures within the ovary wall. The fruit of legumes (redbud, yellow wood, wisteria, locust, pagoda tree, coffee tree, baptisia, lupine, scotch broom, green bean) is an elongated pod (ovary) which at maturity often dehisces along two suture lines; the green bean-shaped seeds attached to the interior (ovary wall). The hard seed (not always) coat encases the mature embryo and cotyledons. Each legume species may require different pretreatments to facilitate/promote germination.

Osmanthus species have bowling pin-shaped pistils. The top designated the stigma, often sticky/viscous, where the pollen alights, the style is the neck of the bowling pin where the pollen tube continues to elongate, until it disperses the sperm cells into the ovary (bulbous basal part of pistil) where the egg cells are fertilized, thus forming the forerunner of the seed. The fruit is derived from the ovary (usually) and at maturity manifested in many shapes/structures including achene (abelia), berry (honeysuckle, persimmon), dehiscent capsule (forsythia, fothergilla, rhododendron, witch-hazel), drupe (osmanthus, holly, fringe tree, hawthorn), follicle (magnolia), nut (hickory, oak, walnut), pod (redbud, wisteria), pome (apple) and samara (ash, maple, elm). Each fruit requires different strategies for collection times, drying, cleaning, seed extraction, storage and pretreatments to facilitate germination.

The fruits of the Hamamelidaceae are two-valved capsules that dehisce at maturity. Distylium, Fothergilla, Hamamelis, Loropetalum and Parrotia fruits mature in fall (September-October, Athens) and must be collected before the capsules dehisce and the seeds ejected. I collect these when the capsules turn green and before turning brown with no open/suture lines showing, place them in large paper grocery bags/closed boxes in the office, and within a few days hear a popping sound: the seeds ricocheting off the sides. Clip the top of the bag for the seeds will be ejected through the opening. The seeds are brown to black; football shaped with a leathery outer coat. They are cleaned, stored in glass jars at ~41°F with silica gel packets to absorb moisture until processing for stratification treatments. This storage treatment is standard with most seeds at Premier Introductions, Inc. (PII).

Buddleia, Deutzia, Hydrangea, Philadelphus and Rhododendron bear dehiscent capsules with extremely small seeds. All can be sown immediately and will germinate without pretreatment. Buddleia seeds are thin and stringy, floating on the slightest breeze. When the capsule turns brown and there is a minute split at the top end, carefully collect the entire infructescence, holding it upright and insert it into the paper bag. This approach applies to any dehiscent capsule. If the capsule (indehiscent) does fully open, I use a rolling pin to fracture the ovary wall which releases the seeds.

Fleshy fruits like holly, flowering dogwood, gardenia, magnolia and nandina are soaked in water until soft. Fruits are placed on screens and/or thick paper and the seeds pressed out, dried, then stored as above. A rolling pin is also used to squish seeds from the fruit. On occasion a blender at slow speed with blades wrapped macerates the fruit, the seeds sinking to the bottom of the slurry. This latter approach is effective with hard coated seeds like holly and blueberry. There are commercial cleaning machines for processing large seed quantities.

For large fruits/seeds such as oaks, hickories, and buckeyes the husks/caps are removed and seeds either stored for short periods or planted immediately and covered to protect from critters. Buckeye and horsechestnut seeds do not store well because of the large endosperm. They shrivel quickly if not kept moist. Containers/flats are left outside with nature providing the necessary dormancy breaking requirements for germination.

Guidelines for collection, viability, storage, stratification

When are fruits/seeds mature?

The standard definition is when there is no gain in fresh or dry weight. At this stage the embryo and storage tissues (endosperm, cotyledons) are/should be fully developed. Color is a reasonable indicator of maturity with oaks developing the characteristic brown/black shell. However, I collected green acorns of Q. × bimundorum Heritage (8-28-19), planted immediately, with excellent germination in spring. Caveats apply as holly embryos may not be fully developed and require a warm after-ripening period to fully develop before they are receptive to cold stratification stimuli.

How to determine if seeds are sound/viable

The easiest way is a cut test. Take random samples of ~10 fruits/seeds and cut them in half to see if solid. Many maples, paper bark, three-flower, and sugar, when cut, are hollow. In the Dirr garden, two different sugar maple clones, growing side by side, have yet to produce a viable/full seed.

Another approach is to float fruits/seeds. Sinkers are usually viable and floaters often not, but not always. Oaks, if solid/viable, will sink like lead weights. Many fruits like maples do not sink.

I seldom see references to the tetrazolium test which is a colorimetric indicator of viability. Seeds (Initially soaked then cut, nicked, interior exposed) are soaked in a clear solution of tetrazolium chloride in the dark. If viable, the seeds develop red coloration.

If in doubt about viability and, with few seeds to test, perform the recommended stratification treatments and plant.

Storage

I prefer glass jars to plastic bags/containers. Labeling is important as lids and jars are marked with plant type, if crosses (parents), date/where collected, when cleaned, and stored. Silica gel packets are included with seeds to absorb moisture. Canning jars work well as new lids are readily available and make strong seals. I mentioned ~41°F for storage temperature. It is important to maintain moisture content. Don Allen, F. W. Schumacher Seedsmen, Sandwich, Cape Cod, Massachusetts, recommends 34 to 38°F and less than 10% moisture content. He noted the most important thing is to have a good gasket to seal out air and know the moisture percentage of the seed. Small seeds like Hydrangea species are prone to dry in storage, although seeds of H. quercifolia germinated in high percentages after two years. Asclepias tuberosa germinated in high percentages after nine years of storage. Seeds of Aesculus spp. dry and shrivel within a few weeks if not stored or planted.

Pretreatment/stratification

Seeds (cleaned and/or stored) are ready for sowing or preconditioning treatments that release them from dormancy. Many woody species can be sown as soon as collected/cleaned/soaked including Buddleia, Cercidiphyllum, Caryopteris, Deutzia, Hydrangea and Vitex. Calycanthus, Chamaecyparis, Loropetalum and Magnolia require cold moist treatment for 30 to 90 days. Within Chamaecyparis species, cold periods vary. Chamaecyparis obtusa germinated in high percentages after 60 days cold. Chamaecyparis thyoides may take up to 180 days. In fact, C. thyoides ‘Glauca’ seeds collected from UGA campus trees germinated in high percentages after six months cold stratification. Recalcitrant genera/species like Chionanthus, Fothergilla, Ilex, Osmanthus, Stewartia, Styrax and Viburnum require periods of warm followed by cold and perhaps another cycle to facilitate germination. I germinated seeds of this latter group and, in recent years, resorted to sowing seeds (fall) in flats/containers, placing them outside in plastic storage containers and observing for seedling emergence in spring. Flats are then brought into the greenhouse. This approach is excellent for Acer palmatum.

Sowing and/or prepping seeds for stratification

Well drained germination mix is the ideal. PII uses Sun Gro seed germination formulation with peat:perlite:dolomitic lime and wetting agent. It has consistently outperformed any other product PII trialed. For large seeds/nuts like oak and buckeye, bark media is used. Seeds/nuts are sown one-half to one-inch deep, 5 to 10 per 3-gallon container, placed outside, covered for critter protection, with germination ensuing in Spring.

I firmly believe in soaking seeds before sowing or stratification. A seed must be primed with water before it travels the road/path to germination. Even seeds that float (remain on the surface of water) should be submerged/soaked. Simply take a smaller glass or plastic vessel and insert it into the larger with the seeds to submerge them. The most quoted soaking time is 24 hours with 48 hours max. I purchase woody seeds from Sheffield Seeds and F. W. Shumacher, and they recommend soaking almost all seeds. I use warm water initially as the molecules are moving faster and more readily imbibed/absorbed. Imbibition is a word seldom used but refers to a largely non-active, non-energy driven process, based on total randomness. Once water is imbibed, the metabolic processes (fat, oil, carbohydrate breakdown; enzyme activation: proteases and amylases; cell division and differentiation; swelling/fissuring of seed coat structure) are engaged, leading to germination and seedling growth.

Scarification

This is the process of breaking/fissuring hard seed coats to facilitate water imbibition. Seeds of legumes like Gymnocladus dioicus, Kentucky coffeetree, possess extremely hard seed coats and are notoriously slow to imbibe water. The seed coat can be degraded by filing if a few seeds are in play. Seeds soaked in concentrated sulfuric acid for 0, 2, 4, 8,16 and 32 hours germinated 7, 93, 100, 95, 82 and 87%, respectively. This is the last course of action (for me) to break/rupture the seed coat and permit water imbibition. I would always opt to soak seeds in water before employing acid treatments.

Seeds can be sown after soaking assuming they do not require stratification treatments. The stratification medium should hold water but never too much that oxygen is excluded (anaerobic conditions). Sand is the preferred medium at PII, usually white sandbox type, that when moistened turns light brown. However, any moist medium will work. Seeds are mixed thoroughly with the moistened sand in clear plastic bags labeled with names, dates, and stratification times. If warm stratification must precede the cold, bags are kept at room temperature and checked weekly. When the warm period is completed, they are moved to the cold for the required time.

The warm period facilitates embryo development, allowing the seeds to germinate, or brings the seeds/embryos to physiological maturity so that the cold period can effectively satisfy the dormancy requirement. Apparently, an immature embryo does not respond to the cold treatment/stimulus.

Seeds may germinate in the bags and should be immediately sown. Nandina domestica seeds require warm stratification with root radicles developing after a month or two. Seeds of ‘Gulf Stream’ in warm stratification on Nov. 13, 2022, germinated in the bag on Jan. 7, 2023. Seeds of Planera aquatica, water elm, placed in warm stratification April, 17, 2018, germinated in the bag May 9, 2018. Loropetalum chinense var. rubrum ‘Little Rose Dawn’ placed in cold stratification Nov. 4, 2022, germinated in the bag Jan. 20, 2023. The recommended cold stratification time for Loropetalum is 60 to 90 days. The key is to check/monitor the bags on a regular basis, so seedlings do not become etiolated (yellow/white).

For double dormant seeds like Stewartia, Styrax, and Viburnum, ideally sow in flats. Place outside in late summer/autumn, check for moisture, and wait. The process can be accelerated by utilizing bags and moving seeds from warm to cold for two cycles.

Seeds do not exactly follow textbook prescriptions. I germinated seeds of Ilex glabra Forever Emerald, a compact inkberry that holds foliage to the base in the hope this trait would be expressed in the offspring. Seeds were sown in flats (Nov. 27, 2023) and placed in tubs outside with seven resultant seedlings (April 8, 2024). Seeds (pyrenes, specialized drupes) are small and seedlings fragile. For a second batch of seeds, I asked John Ruter, UGA Horticulture, who has an excellent track record with Ilex breeding, how he manages seed. Ruter said to try two months warm (Nov. 17, 2023) followed by two months cold (Jan. 28, 2024). After these treatments, the bag was then placed at room temperature; the seedlings germinating Nov. 27, 2024. Four trays were then sown with five seedlings evident on Dec. 9, 2024: 54 seedlings on Jan. 15, 2025 and several seedlings germinating on Feb. 2, 2025. The final tally was 64 transplanted seedlings. In seven months, the seedlings grew vigorously after transplanting to 3-gallon containers and were distinctly different from the parent.

The take-home lesson is patience for seeds operate on their intricate and innate biological time clock. The practices discussed herein serve as prompts to bring seeds to a stage of germination readiness. Consistent results are not guaranteed.

For accurate/reliable instructions on seed germination protocols for numerous species I recommend Sheffield’s Seeds, Locke, N.Y. and F. W. Shumacher, Sandwich, Massachusetts. The Reference Manual of Woody Landscape Plants (2006, Timber Press, available on Amazon) includes chapters on seed, cutting, grafting/budding and tissue culture with a chapter detailing germination specifics for each species from Abelia to Ziziphus.

Explore the January 2026 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Nursery Management

- Jackson & Perkins expands into Canadian market

- Green & Growin’ 26 brings together North Carolina’s green industry for education, connection and growth

- Marion Ag Service announces return of Doug Grott as chief operating officer

- The Garden Conservancy hosting Open Days 2026

- Registration open for 2026 Perennial Plant Association National Symposium

- Artificial intelligence applications and challenges

- Fred C. Gloeckner Foundation Research Fund calls for 2026 research proposals

- Harrell’s expands horticulture team with addition of Chad Keel