Photos by Vanessa Rivas

After a long, sweltering summer, the atmosphere at Windmill Nursery crackles with excitement and anticipation.

Windmill Nursery is thriving despite a crippling drought, rising inflation and a shaky economy. Its client portfolio of garden centers, rewholesale customers, and landscape contractors across a third of the U.S. seek out the Franklinton, Louisiana-based nursery’s container-grown shrubs, perennials, trees and ground covers. And demand is intensifying.

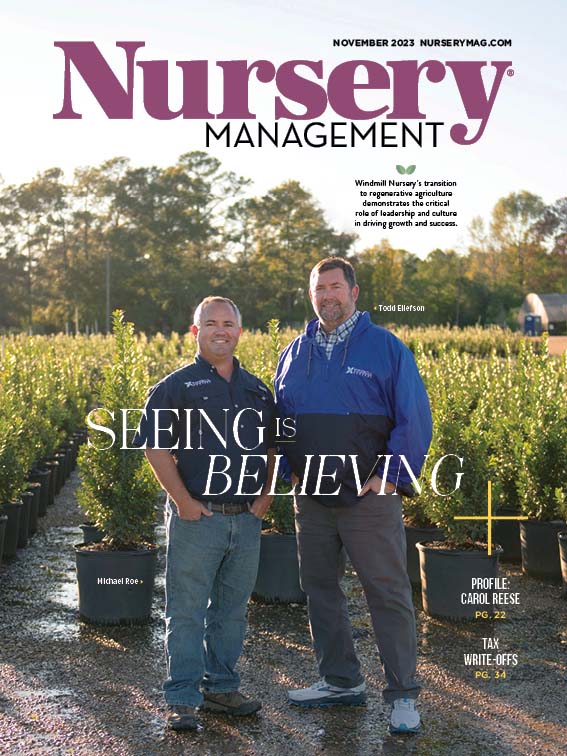

Windmill recently transitioned from a conventional to a regenerative pest management practice. Under the guidance and vision of vice president of production Michael Roe, Windmill adopted a soil-first philosophy focused on nutrition and providing a sound growing medium for its plants.

“The fact that we just went through this major heat wave, lack of rain, the drought, and the plants in our nursery still look good is a testament that these practices work,” Roe says. “And we’re more profitable than we’ve ever been. We’re turning crops out faster with fewer inputs — and less dollar amounts of inputs — to get the plants to the finish line. It’s unbelievable.”

Windmill Nursery's story is more than just about a successful transition to regenerative agriculture. It is also a testament to the power of strong leadership, a supportive team and company-wide buy-in, even when the path ahead is uncertain and challenging.

An old gameplan

About 10 years ago, at an industry show in Mobile, Alabama, Roe was talking shop with an old boss from his days at Cherrylake, a Central Florida tree farm, lamenting his pest issues, including a battle with spider mites.

“So, he told me to spray kelp,” Roe says. “I asked him if he’d lost his mind. So, he wrote down seven books for me to read and told me to call him back when I finished.”

And Roe did just that, ordering those books, many of them tomes from the 1950s and 60s, that took a more holistic than chemical approach to plant health practices. Within a month, he was calling for more reading suggestions, eager to implement what he had learned.

Roe also followed his colleague's advice to spray liquid kelp for spider mite control and was stunned by the results.

“I had some variegated pittosporum in a propagation house that was so bad with mites you’d have thought they were just spider webs,” he says. “So, I sprayed them and forgot about them. A week later, my pest control guy called me out. Everything was gone. The eggs were gone. Everything was gone just from that kelp [spray]. I knew we were on to something.”

And after 8,000 red tip photinia became infested with Entomophobia leaf spot — a fungus that causes premature leaf drop — days before 3,000 of them were scheduled to be shipped to Virginia, Roe knew that the conventional chemical approach had failed him. Ditching the “traditional” chemical route, he developed a solution focused on better nutritional practices and soil composition.

Inspired and encouraged by his newfound knowledge and passion, Roe began converting Windmill to regenerative practices, prioritizing soil health and using organic over synthetic inputs. Confident he could produce results, Roe progressed from small trials to nursery-wide adoption over the course of the next two years.

“I didn’t want to alarm everybody by saying we were going to try something new,” Roe says. “So, I kinda started under the radar and just started tinkering with it. When I saw it performing, I announced here’s what we were doing and the [goal] we’re moving towards. We’re going to drop neonics because we don’t need them, and we just proved it out. And we don’t need glyphosate anymore, either. From there, we moved on to a larger scale [integration].”

And there were initial hesitations, Roe admits. Could he consistently achieve high-quality results with a sustainable approach? Could it be cost-effective?

However, Roe’s carefully calculated risk paid off. As a result, Roe describes Windmill’s crops as having a truer, more natural color, as opposed to what he describes as the artificial intensity produced by synthetic nitrogen and excess potassium. In addition, he says the plants flush new growth over much more extended periods instead of the initial burst that then waits for the next shot of synthetic nutrients to flush again.

Roe says that from a financial perspective, organics are less expensive than conventional products. Windmill uses 75% less chemical insecticides, miticides and fungicides; 40% less herbicides than it did before nursery-wide adoption of Roe's practices, which he says translates to around a 35% to 40% cost decrease. In addition to monetary savings, Windmill brings to market healthier and more sellable products with fewer undesirable plants. And then there are the intangible benefits, such as the positive impact on bees and other pollinators and creating a safer work environment.

“We still have some problems, and we’re not flawless by any stretch,” Roe adds. “But we’ve proven we can get product grown quicker and available [for market] a lot sooner for less money and labor. And the quality has gotten better than it ever has been. All of this is a testament that this [process] works.”

While Windmill’s regenerative program continues to evolve to address new challenges, its foundational principles remain intact. So, what does Roe’s process involve?

Roe explains that growing mixes remain relatively simple, consisting primarily of pine bark and blended with supplemental gypsum, lime and soft-rock phosphate. Windmill’s propagation mix is an 85/15 mix of pine bark fines and perlite, respectively, and the nursery mixes its own soil.

Roe still relies on a small amount of Nutricote 18-6-8, a controlled-release homogeneous fertilizer with macro-nutrients and essential micro-nutrients, to ensure plants grow evenly, and supplements with organic nutritional and microbial foliar sprays from Advancing Eco Agriculture. It’s an ongoing process to dial in and tweak nutritional programs for the various plant species Windmill produces.

Plants in propagation receive mycorrhizae to strengthen root systems and improve plant nutrition. Newly potted crops are sprayed with microbes, which are watered in to get them into the soil and promote a solid root mass.

Natural products are always the first line of defense at Windmill for insect mitigation to control the occasional aphid and white fly outbreak. Red-headed flea beetles continue to be a problem that receives attention via plant nutrition. And any conventional pesticide application is accompanied by a nutritional solution to strengthen the fertility program, Roe says.

And despite its location in the steamy south, fungal issues are rarely a problem, which Roe attributes to Windmill’s nutritional practices and strong plant health.

Leadership

Windmill Nursery has a rich history. It’s family-owned, with five generations leading the company over its 100-plus-year history. President Todd Ellefson, the great-great-grandson of legendary nurseryman and founder John Wight, has been working in some capacity in the family business since he could walk and has been in upper management since 2003. Under his leadership, Windmill has doubled in size and scope thanks to an ambitious growth strategy.

Ellefson subscribes to a macro-management philosophy, a leadership style that empowers employees to take ownership of their work and make decisions. He provides them with the context and resources to prioritize and execute high-impact work and achieve high-level results.

“You cannot micromanage a nursery, and you have to let the leaders that you put in place make decisions and support those decisions,” he says. “It’s hard, and change is tough, but if you don’t let them have ownership and show you support them, then you’re always going to micromanage the business.”

“You want your people to feel they have the ability to make the changes that will impact the nursery for the better,” he says, adding that it’s crucial to encourage risk-taking for the greater good and not just to appease ownership. “It’s not about Todd. It’s about Windmill Nursery.”

This approach fosters one of Windmill’s greatest strengths: an open culture encouraging employees to challenge the status quo and seek innovative ways to improve. This top-down support was essential for Roe to take the company in a new agronomic direction.

“I knew how strongly [Michael] believed in what he was proposing for the nursery, and he was willing to take ownership of that decision,” Ellefson says. “So, I had to be willing to give him the authority to do what he believed was right first on a trial basis and then full-time. It was as much me supporting him as him supporting me and, together, what we wanted to achieve for the nursery.”

Was Roe’s process perfect from start to finish? Absolutely not, Ellefson says. New approaches are bound to have hiccups, but this is expected.

“Anytime there’s change, in this case eliminating one practice for another, you’re going to have some regression as you move forward,” Ellefson says. “For us, it was always a question of how do we move forward and continue to buy into this to make our nursery greener?”

Ellefson knew he needed to provide unwavering support, even in the face of setbacks. He recognized he was setting the example for others to follow during the process.

“Certainly, there were times when I just kind of scratched my head and asked [Michael] to sit down and help me understand a little better what he was trying to achieve and how that was going to get us in the direction that we were wanting to go,” Ellefson says. “But the big thing in all of this is that the upper management group at the nursery and I have a close enough relationship that we’re open with one another about decision-making, where the problems are, and how we need to move forward [to address them]. We talk our way through the problems to better understand the solutions. This has been vital in this process and in achieving all our success.”

The culture

The shift to regenerative agriculture could be a tough sell to Windmill's team members, especially the sales staff who were on the front lines with clients and consumers. They would bear the brunt of any product that failed to meet plant quality, health and longevity expectations.

Although admirable, sustainable and environmentally sensitive growing practices only influence a small fraction of consumers.

“It takes a lot to sell this whole idea to the consumer,” says Henry Hunter, Windmill’s vice president of operations. “People who are plant people, they get it. They understand, and they want this [holistic approach]. But you also have people who just want [to purchase] a clean plant. And that can be a challenge.”

The knee-jerk reaction to a change like this is often, “If it's not broken, why fix it?”

“Everybody is on board on paper until there’s a problem,” Hunter adds.

Early on, Roe encountered complications — bouts of disease or insect infestations — as he perfected his practices. Some team members suggested reverting to conventional methods, and Roe had to resist the pressure.

“It would have been easy to back down and say, ‘Okay, you’re right, let’s go back to the way it was,’” Roe says. “But I wasn’t going to back down.”

Such a philosophical pivot was bound to be accompanied by a few agricultural challenges, says Jack Gearing, Windmill’s sales manager. While clients understood that Windmill was moving in the right direction, they had questions when they received products that were still being fine-tuned or had quality issues due to disease pressure.

“[Sales] reps would hear [negative feedback] and say, I don’t know why we’re doing this. Let’s just nuke the place, kill all the bugs and get everything right,” Gearing says. “But as a management team, we felt [this new approach] was the right thing to do. Michael was passionate about it, and the whole team wanted to keep pushing it forward.”

Despite the learning curve and some initial pushback, the proof of concept is evident in Windmill’s final product, which consistently gets better and better, Gearing says.

“Over the last four years, the jump in the quality of our product has been significant, and we took an even bigger jump in the last six to eight months,” he says. “I recently toured the nursery, and we were still in drought and extreme heat conditions. I expected to see a bunch of stressed-out plants and a lot of death and loss of material. But the plants look like they have spring flush on them. They’re healthy and vibrant. They look great.”

Windmill’s paradigm shift to regenerative agriculture proved that doing things more holistically was not only a responsible pursuit but also profitable. They also learned to navigate risks and overcome obstacles as a company. This newfound resolve enabled them to pursue an aggressive strategic growth plan over the next five to 10 years.

And whether it was realized at the time, Windmill also required a shift in the company’s cultural makeup. In fact, substantial change has taken place over the last seven years. Gearing says many people have come and gone to get the right personnel with the right mindset in the correct positions. An organization can have people who do more harm than good, and it’s imperative when building a successful team to have the right people in place who own their jobs. And that philosophy extends from the management team to the guy in the field who is pulling plants, Gearing says.

“It’s about getting the right people to work together,” Gearing says about growth and success. “You want people who can disagree but not hold it against each other; it doesn’t get personal and stays on a business level. We’re all working toward the same goal.”

As the company’s leader, Ellefson allows his team to run things as they believe they should.

“Todd periodically points us in a direction toward the goal, and then he pretty much gets out of the way and lets everybody do their thing,” Hunter says. “And I really doubt that there are many companies of similar size and similar mission that have as much freedom in their departments as we do. We’re allowed to exercise a lot of freedom, and that’s worked out well [for Windmill].”

For the next five to 10 years, Windmill’s goal is to continue its growth trajectory by adding acreage and production, increasing its field reps, bringing on the next generation of managers, and exploring new Northern and Midwest markets for its plant products, which are also expanding.

“When you look at all of this from the growth of Windmill Nursery, we’ve done the right things and added the necessary pieces to ensure we don’t fall behind and only progress forward,” Ellefson says. “As a company and as a team, we’ve done a great job of putting the right people together for success. From me on down to the guy in the field, we’ve all come together to make this happen.”

In many ways, Windmill is a new model for the modern nursery.

“Anybody not moving in this direction is doing themselves a disservice,” Hunter says. “The world is certainly going that way … and we’ve really been ahead of the curve, which will pay off in the end.”

“We’ll still have roadblocks, and we’ll still have issues that we’ll have to correct,” he adds. “But we’re headed in the right direction. And 10 years down the road, we’re going to be really, really successful for getting on board with [these practices, changes and improvements] as early as we did. And with Todd’s vision, Jack’s leadership and Michael’s methods, success will continue to be in our future.”

Explore the November 2023 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Nursery Management

- Redesigning the product and process

- GS1 US Celebrates 50-Year Barcode 'Scanniversary' and Heralds Next-Generation Barcode to Support Modern Commerce

- University of Florida offers Greenhouse Training Online program on irrigation water

- Tree Fund announces scholarship and spring cycle grant awardees

- ‘Part of our story’

- Asimina triloba

- Oregon Association of Nurseries announces death of Jolly Krautmann

- Dramm introduces new hose, sprinkler attachments for home gardeners, nurseries