Photos by Stephen Ward, Oregon State University

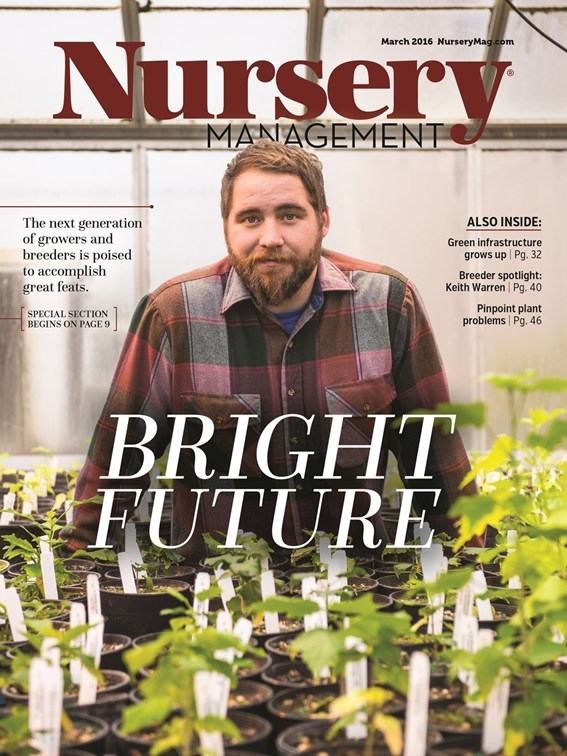

Justin Schulze took a unique path on his journey to a horticulture career. When someone close to him was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, Schulze immediately began researching the disease and possible treatments. He discovered that patients were using cannabidiol (CBD) to successfully treat not only the symptoms of Crohn’s disease, but the disease itself. He was living in Portland, Ore., at the time – a state with access to a medical cannabis system.

The owner of an analytical mind, Schulze set about learning how to cultivate medical marijuana.

Although he had always enjoyed being outdoors and in nature, the 28-year-old who hails from Queensbury, N.Y., had never considered horticulture as a potential career before. But growing medical marijuana sparked an interest he never expected to have.

“I fell in love with the whole activity of it, making these things grow was fun and interesting,” Schulze says. “Applying nutrients, trying to manage pests — the whole deal.”

He became a licensed grower in Oregon’s Medical Marijuana Program. From there, he furthered his horticultural education, broadening his range to other plants. Propagation in particular was his favorite part of the process. As he worked with medical marijuana, though, he noticed the differences in CBD products. And he started to entertain the thought of becoming a plant breeder.

“I know there is development of no-or-low-THC and high-CBD strains, and I think that if there is a medical future of this plant in this country, that’s where it’s going to be,” Schulze says. “I have always been a math person, so breeding and genetics is the perfect place for me in the field.”

He had been searching for a graduate program to further his education. A bachelor’s degree in biology was a good start, but he needed a more specialized degree. The Ornamental Plant Breeding program at Oregon State University seemed like a perfect fit. Ryan Contreras, an assistant professor at OSU and Schulze’s current advisor, offered a program aimed at reducing fertility of ornamental plants so they would be less invasive in the environment. That appealed to Schulze, who had previously worked for an environmental company with an ecological focus.

Schulze and his group of fellow students often interact with Oregon’s nursery industry. Field trips are common, and the university even has its own field day, during which growers visit the class and provide feedback on the program. Schulze says the goal is to get as much input as possible from nurserymen to figure out what problems they face, what their goals are, and what the students should be working toward.

These interactions were the genesis of Schulze’s research into common cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus). Some of Schulze’s work is focusing on embryo rescue and tissue culture of the widely-produced nursery crop with the goal of improved disease resistance.

“We’re trying to create interspecific hybrids of two different types of cherry laurel to try to introgress disease resistance to shot hole disease,” he says. “Because every time I talk to a nurseryman and say, ‘I’m working on common cherry laurels,’ they ask ‘Are you working on shot hole?’ Now I can actually say ‘Yes.’”

The Portuguese cherry laurel doesn’t show symptoms of shot hole disease. Through chromosome doubling and increasing the ploidy level, Schulze is trying to breed a hybrid that keeps that resistance intact. It’s a difficult cross, but he’s hopeful.

“If there were a cultivar that didn’t exhibit the symptoms, that would be a big deal for the nursery industry,” Schulze says. “That’s the main target of the cross. But there is also the idea that this interspecific hybrid would produce a sterile cultivar, which is another goal of the program. That would reduce the ability of it to escape cultivation and become naturalized in the environment.”

Explore the March 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Nursery Management

- GardenComm 2024 Annual Conference registration is open

- Landmark Plastic celebrates 40 years

- CropLife applauds introduction of Miscellaneous Tariff Bill

- Greenhouse 101 starts June 3

- Proven Winners introduces more than 100 new varieties for 2025

- CIOPORA appoints Micaela Filippo as vice secretary-general

- Rock Star Roses

- The container challenge